Benjamin Labautut’s When We Cease to Understand the World electrified a global readership. Throughout the selection of non-fiction novels I found myself in the history of the science and technology tyrannical forces that keeps confronting us with the deepest questions about the truths in human nature.

In Maniac, Labatut as created a tour de force on greater scale. It begins with Paul Ehrenfest- an Austrian physicist and friend of Einstein’s and places the Neumann at the center of a literary triptych. A prodigy whose gifts terrified the people around him, John van Neumann transformed every field he touched, inventing game theory and the first programmable computer, and pioneering AI, digital life, and cellular automata.

The industry-defining breakthroughs in design and tech lead the conquer the gaming world. In DOOM guy: Life in First Person, John Romero reveals his personal breakthroughs and vulnerabilities, difficult childhood and storied career. After a years in a gaming spotlight Romero is now shedding the light on the development of his games and business partnerships that made DOOM and Quake cultural phenomena and lead him, ultimately, to be called DOOM guy and a video game legend.

Besides the DOOM, how do we find the courage to rebel against forces ranged against the Earth? Book Poetry Rebellion by Paul Evans embodies a galvanizing collection of poems spanning 4000 years of human history. This book is not just a sanctuary in which to find solace from environmental grief but a manual for psychic resistance in the war against Nature.

“Literature is pathetic.” So claims Eileen Myles in their provocative and robust introduction to Pathetic Literature, all exploring the so-called “pathetic” or awkwardly felt moments and revelations around which lives are both built and undone. Myles first reclaimed the word for a seminar they taught at the University of California San Diego in the early 2000s, rescuing it from the derision into which it had slipped and restoring its original meaning of inspiring emotion or feeling, from the Ancient Greek rhetorical method pathos. Their identification of “pathetic” as ripe for reinvention forms the need for this anthology, which includes 106 contributors, encompassing canonical global stars and extraordinary writers.

Destined to Doom

Now we had time and resources to breathe, think and dream. At one of the first meetings, someone asked about a possible title for the game. Carmack said he had the perfect name.

“I was watching the movie The Color of Money”, he told us.

We were all familiar with it. It’s the one starring Tom Cruise as a pool hustler.

“There’s a scene where Cruise walks into a pool hall with his cue case and hands over some money to challenge another guy. So, the guy looks at Cruise and says, ‘What you got in there?‘”

The camera then pans up to Cruise, who has a confident, ear-to-ear smile, Carmack had the same smile on his face. “And Cruise looks at him, smiles, and says ‘In here? Doom.‘”

Technology should enable, serve, and inspire design, and vice versa. So ideally, when a game designer talks about their vision, the technical architecture should begin to formulate in the brain of the engine architect. Technical specs must be mapped not only to optimize the look, speed, and efficiency of the engine but to deliver the best gameplay, too. When there is planning, discussion and dialogue, engine architecture evolves with the demands of a game, but development can work the other way too, because an engine creates new gameplay opportunities.

My point is that while the DOOM engine was unquestionably a phenomenal achievement, Carmack didn’t just say “Here, use this.” DOOM was a collaborative effort. As the possibility space for gameplay began to take shape after the first few meetings, I wanted to make sure everyone realized the opportunity we had. We had all seen Carmack do the undoable multiple times, so it was time to think big. Really big. I wanted each one of us to do the undoable. I delivered an impromptu mission statement for the project:

“We need to make this game the best thing we can imagine playing. We have to think of all the amazing things we’ve never been able to do and put them in this game.”

Over the Christmas break, while the rest of us headed home to visit our families, Carmack stayed in Wisconsin. He was expecting a package, cash-on-delivery: an impressive workstation, the NeXTstation by Steve Job’s new company, NeXT Computer. The machine used the incredible NeXTSTEP operating system, which was light-years ahead of MS-DOS. It was the future. Carmack ordered one and needed to get an $11,000 cashier’s check for the delivery guy, but with his MG left for dead in Shreveport and all of us out of the town, he trudged to the bank on foot, cursing the snow, ice, and freezing temperatures the whole way.

Destined to Doom, Doom Guy: Life in First Person (p156), John Romero.

One afternoon in the 1840s, as George Boole walked across a field near Doncaster, a thought flashed into his head that he believed was a religious vision. Boole suddenly saw how you could use mathematics to unlock the mysterious processes of human thought. The same symbols that were used in algebra could be used to describe what went on inside people’s heads as they followed a train of thought, expressing all the twists and turns in simple binary form. If this, then that. If that, then not this. And in 1854, Boole wrote a book that caused a sensation. It was called An Investigation of the Laws of Thought. Its aim, “to investigate the fundamental laws of those operations of the mind, by which reasoning is performed”… Boole was driven by an almost messianic belief that he had been allowed a glimpse, by God, into the truth of the human mind. But there were those who doubted this; the philosopher Bertrand Russell was astonished by the brilliance of Boole’s mathematics, but he didn’t believe what Boole had discovered was anything to do with human thought. Human beings, Russel said, do not think like that. What Boole was really doing was something else…

Adam Kurtis, Can’t Get You Out of My Head

The Limits of Logic

I often wonder if my horrific inferiority complex, which not even the Nobel Prize has diminished in the slightest, is a product of having known von Neumann for the better part of my life. Growing up he was not shy, introverted, or ill at ease in his own body, and in that sense he was unlike any other genius I ever met, but as a child the most unusual things confounded him, things that would never bother a normal boy: he confessed that he could not understand how he had learned to ride a bicycle- a veritable feat of balance, equilibrium, and coordinated motor function- without once having had to use his reason. How could his body think by itself? How could it figure out the complicated motions that it had to execute so as not to fall flat on his face? These simple activities, in which you actually had to stop thinking to fully accomplish them, would fascinate him for his entire life, and even though he loved sports when he was a boy, he avoided all forms of physical exertion when he became a man. Klari took him on a skiing trip once. She had been a champion figure skater in her youth in Budapest and moved about with such grace that Jancsi looked like a tiny chauffeur or a bellboy following her around. He said yes to the invitation and went along tamely enough, but after going down the first run he threatened divorce and spent the rest of that weekend getting drunk and working out some fantastic scheme to heat the planet’s weather and ensure a tropical climate all over the world.

Although I would later devote my entire life to physics, in school I was an aspiring mathematician, so I knew just barely enough to intuit Jancsi’s unbelievable talent: he explained set of theory to me- the basis if modern mathematics- in such a simple and clever way that I still find it hard to believe that he could have had such a profound understanding before he had even began to shave. Jancsi was trying to make sense of the world. He was searching for the absolute truth, and he really believed that he would find a mathematical basis for reality, a land free from contradictions and paradoxes. To do so, he was determined to such understanding out of everything. He read voraciously and studied day and night. I once saw him take two books to the toilet, for fear that he might finish the first one before he was done.

Being Close to Data

You can’t see the forest, the pandemic

for the trees, our everyday lives

and thank god for that as it is as it is

I’m never in the mood for a pandemic

to take up residence in my brain

it is not in me to take up thinking

of people as nothing but numbers

to be counted for the story to grow ever

more and more awful and for the public story

to be gotten under whose control

If this were a data love poem

I’d be tearing out my hair and ranting

against just who thinks they can take this

from us with so little visible at our peril

without our permission as if in this case

now is not sufficiently present and we

who are here now will acquiesce in silence

Being Close to Data, Dara Barrois/Dixon, Poetry Rebellion: Poems and Prose to Rewild the Spirit, Book by Paul Evans

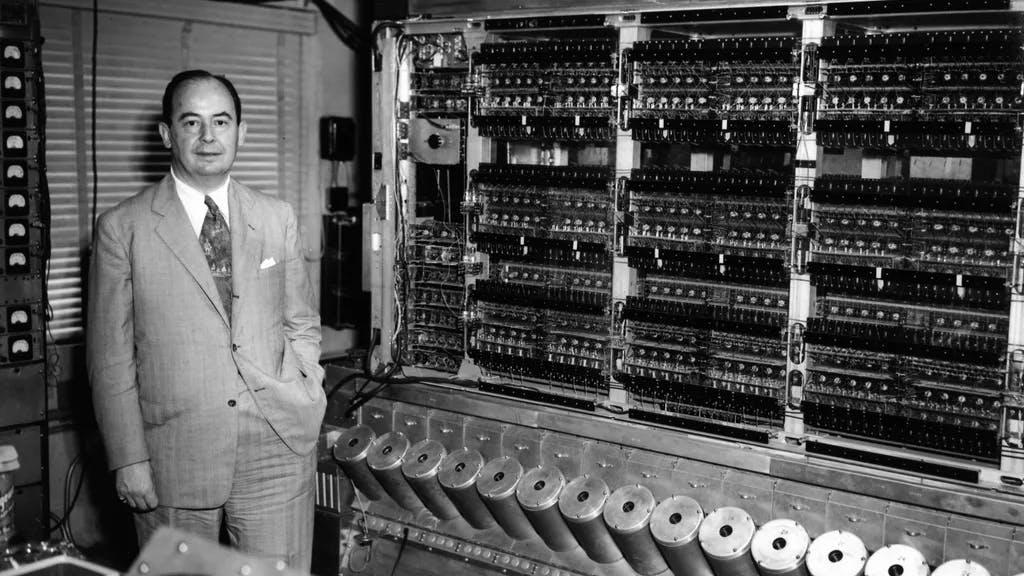

When a cancer spread to his brain and began to destroy his mind, he was sequestered by the United States military and confined to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Two armed guards stood outside his door. No one was allowed to see him without express permission from the Pentagon. An Air Force colonel and eight airmen with top secret clearance were assigned to assist him full-time, even though there were days he could do nothing but rage like a madman. He was a fifty-three-year-old Jewish mathematician who had emigrated from Hungary to America in 1937, and yet at his bedside, hanging on his every word, sat Rear Admiral Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission; the Secretary of Defense; the Deputy Secretary of Defense; the Secretaries of Air, Army and Navy; and the military Chiefs of Staff- all waiting for a final spark, one more idea from the individual who had birthed the modern computer, laid down the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, written the equations for the implosion of the atomic bomb, fathered the Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, heralded the arrival of digital life, self-reproducing machines, artificial intelligence, and the technological singularity, and promised them godlike control over the Earth’s climate, now wasting away before their eyes, screaming in agony, lost in delirium, dying, just like any other man. His name was Neumann János Lajos.

Computer pioneer Neumann at a computer in Princeton around 1952. Photo: Alan

Richards / Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center / IAS

Computer pioneer Neumann at a computer in Princeton around 1952. Photo: Alan

Richards / Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center / IAS

Paul or The Discovery of the Irrational

In photo-

Einstein at the home of Leiden physics professor Paul Ehrenfest, June 1920.

Photo by Paul Ehrenfest’s (1880-1933) associate.

In photo-

Einstein at the home of Leiden physics professor Paul Ehrenfest, June 1920.

Photo by Paul Ehrenfest’s (1880-1933) associate.

In July, as the light of the summer started to brighten the skies above his home in Leiden, Paul’s dark mood lifted enough for him to outline the beginning of a new investigation with Hendrik Casimir on one of the great unsolved mysteries of classical physics: turbulence, that sudden phenomenon by which any smooth flowing liquid breaks down into a wild chaos of eddies within eddies, racing in so many reactions at the same time that their moment cannot be predicted by any known model. Turbulence is ubiquitous in nature.

Just like other such things, Nelly explained, that surpass proportion and cannot be likened to any other. They obey no measure and refuse categorization, because they exist outside the order that compasses all phenomena. These outliers, these singularities, these monstrosities, will not be governed or compared by means of a number, because they lie at the root of what is disharmonious, chaotic, and unruly about the world. For the Greeks, she explained, the discovery of the irrational was a heinous crime, an act of unforgivable impiety, and the divulgence of that knowledge, an offense punishable by death. Nelly spoke of the two surviving accounts of the Pythagorean sage who defined this fundamental commandment: in one version, the man who discovered the irrational was banished from his community, and his friends erected a tomb for him, as thought he were already dead; in the other, he was drowned at sea by members of his own family, or perhaps by the gods of themselves dressed as his wife and his two children. If you discovered something disharmonious in nature, Nelly explained, something that negates the natural order entirely, you should never speak of it, not even to yourself, but instead do everything within your means to remove from your thoughts, purge your memory, watch your speech, and even stand guard against your own dreams, lest the wrath of the gods fall upon you.

Paul became convinced that he was somehow related to the Pythagorean sage and he began to seeing disharmony and turbulence everywhere. He could no longer distinguish any type of reasonable order to the universe, no natural laws, no repeating patterns, just a vast, sprawling world without a measure, riddled with chaos, infected by nonsense, and lacking any sort of a meaningful intelligence behind it; he could perceive the rise of the irrational in the mindless chants of the Hitler Youth spewing over the radio waves, in the rants of warmongering politicians, and in the blind proponents of endless progress, but he could also distinguish it, ever more clearly, in the papers and lectures of his colleagues, brimming over with supposedly revolutionary ideas that he regarded as nothing but the industrialization of physics. He wrote of his dismay to Einstein- whose youngest son, Edouard, was schizophrenic and had been institutionalized on several occasions, so Paul felt his friend was weighted down by part of his same burdens- decrying in his letter what he saw as a dark, unconscious force that was slowly creeping into the scientific worldview, one in which rationality had become somehow confused for its very opposite: “Reason is now untethered from all other deeper, more fundamental aspects of our psyche, and I’m afraid it will lead us by the bit, like a drunken mule.”

On the morning of the twenty-fifth of September 1933, the Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest walked into Professor Jan Watering’s Pedagogical Institute for Afflicted Children in Amsterdam, shot his fifteen-year-old son, Vassily, in the head, the turned the gun on himself. Paul died instantly, while Vassily, who suffered from Down syndrome, was in agony for hours before being pronounced dead by the same doctors who had cared for him since his arrival at the institute, in January of that same year.

Book The Maniac by Benjamín Labatut

The characteristic of the snow-storm is its blackness. Nature’s habitual aspect during a storm- the earth or sea black and the sky pale- is reversed: the sky is black, the ocean white; foam below, darkness above; an horizon walled in with smoke, a zenith roofed with crape. The tempest resembles a cathedral hung with mourning, but no light in that cathedral, - no phantom lights on the crests of the waves, no spark, no phosphorescence, naught but a huge shadow. The Polar cyclone differs from the Tropical cyclone, inasmuch as the one sets fire to every light, and the other extinguishes them all. The world is suddenly converted into the arched vault of a cave. Out of the night falls a dust of pale spots, which hesitate between sky and sea. These spots, which are flakes of snow, slip, wander and float. It is like the tears of a winding-sheet putting themselves into life-like motion. A mad wind mingles with this dissemination. Blackness crumbling into whiteness, the furious into the obscure, all the tumult of which the sepulchre is capable, a whirlwind under a catafalque,- such is the snow-storm. Underneath trembles the ocean, forming and reforming over portentous unknown depths.

In the Polar wind, which is electrical, the flakes turn suddenly into hailstones, and the air becomes filled with projectiles; the water crackles, shot with grape.

No thunderstrokes; the lighting of boreal storms is silent. What is sometimes said of the cat, “It swears”, may be applied to this lightning. It is a menace proceeding from a mouth half open, and strangely inexorable. The snow-storm is a storm blind and dumb; when it has passed, the ships also are often blind and the sailors dumb.

To escape from such an abyss is difficult.

Excerpts from The Man Who Laughs, Victor Hugo. Pathetic Literature by Eileen Myles.

The Silfra Fault, Iceland

If scuba diving often means hot water and coral reefs, there are exceptions that extends of highly advanced dive and technical dive disciplines. That’s exactly what Iceland offers with the Silfra Fault, where the water stays near freezing all year round at 2 degrees!

Located at the junction of the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates, which are diverging from each other at about 2 centimeters per year, this fault close to Reykjavik is recognized as one of the most beautiful cold-water dives in the world. With its waters’ crystalline clarity providing visibility of up to 100 meters, it offers divers and snorkelers the opportunity to lure between the two mineral walls—an incomparable immersion, even though there is very little marine life. It is the only place in the world where you can dive between two tectonic plates and even touch them simultaneously with both hands!

IN PRACTICE

Anyone can be tempted, either on the surface for non-divers or with scuba diving equipment. Diving facilities are available on-site. Remember to dress warmly under the wetsuit.

100 spots de plongée à couper le souffle - Leydet, Anthony