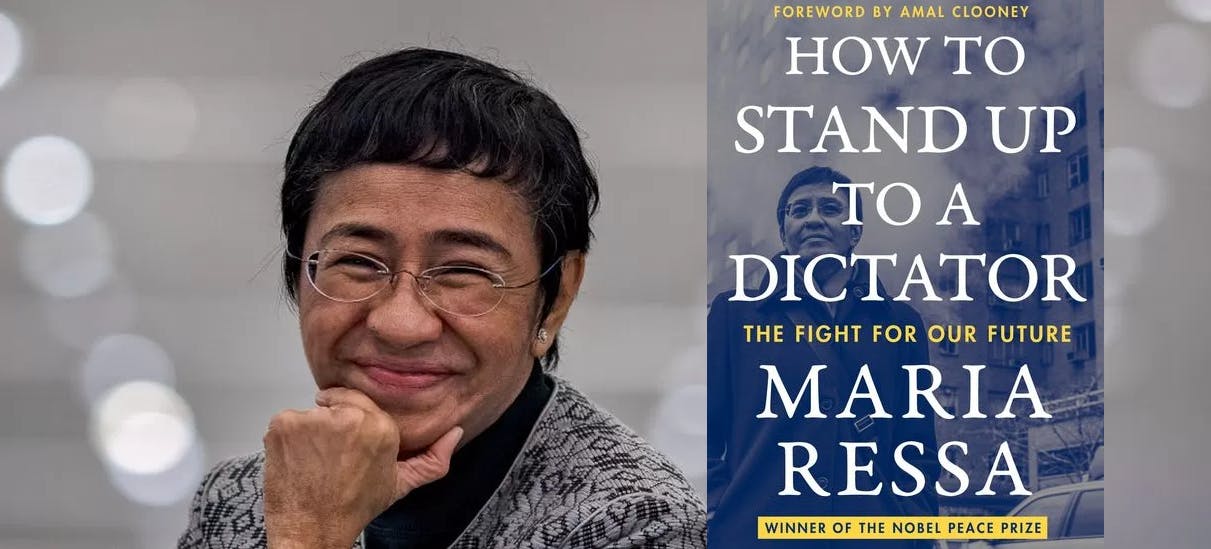

Maria Ressa won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2021

“This is a day that we had hoped would happen sooner. And you know, it went down to these three things, facts, truth and justice. That is who won today.”

A court in the Philippines has acquitted the journalist and her news outlet Rappler of tax evasion, in a move hailed as a win for press freedom. In an interview for the BBC, she talks about “weaponisation of the law” against her – and how it took more than four years to get to this point.

UNESCO’s World Trends in Freedom of Expression Report 2022 highlights these challenges, pointing to the weaponisation of defamation laws, cyber laws, and anti “fake news” legislation, which is sometimes applied as a means of limiting freedom of speech, all of which create a toxic environment for journalists to operate in. What else is there to learn?

Reporters are, like almost all heroes, flawed. As a group, they have a more soiled reputation. They don’t have to spend pages establishing a lack of morals, the mere announcement of the character’s line of work is enough for others to grasp that this person is going to wheedle and deceive. Then there are the lazy- opt for spoon feeding and the facile, rather than the hard, painstaking, often exposed job.

But there is a lot that is heroic, and far, far more of it than most media critiques and institutions would have the beginner believe. There is John Tyas’s exposure for The Times of British atrocities against demonstrators in Manchester in 1819; William Howard Russel’s accounts of the bungling of the British army in the Crimea; William Leng’s exposure in the Sheffield Telegraph of corruption and violence in that city (he was threatened so often that he kept a loaded revolver on his desk and had a police escort home every night); Emily Crawford, who incessantly risked her life to report the 1871 Paris Commune for the Daily News and then scooped the world at the subsequent Versailles Conference; Nellie Bly, who feigned mental illness to get inside an asylum and wrote a series for the New York World that described the terrors and cruelties she found and which led to improved conditions.

There are those whose names are read fleetingly, but rarely remembered; the ones whose efforts to inform their communities are met, not with an obstructive official or evasive answer, but with intimidation or worse. Every year, thousands of reporters are arrested or threatened, imprisoned and killed. In its most extreme form, this is what Peruvial journalist Sonia Goldenburg has called ‘censorship by death’.

All these levels in reporting share something. They may keep it well hidden under the journalists’ obligatory, hard-bitten mask, but the immortals, the persecuted and the unsung all share a belief in what the job is about. This is, above all things, a question.

Neither is a good reporting matter of acquiring a literary ability or a list of tools, but the attitude and character. Some of these attitudes are instinctive, others are learned quickly, but the most are built up through years of experience – by researching and writing, re-researching and rewriting hundreds and thousands of lines. Reporting, similar to coding, is one of those trades that you learn by making mistakes.

In the positive sense of knowing what makes a good story and the ability to find the essential with passion for precision. First- writing accurately and clearly what people tell you while making sure it’s true in the given situation and events, which means adding a background, but not making assumptions- find out what is missing. That way will bring a new perspective and will avoid inaccurate, dishonest and misleading behavior. A determination not to be defeated by a few unanswered calls or stonewalling sources is a hallmark of a decent work. What makes it good is a determination to go that little bit further or longer.

Psychological resilience is required. Your work will often be judged at speed, and in public, by editors or other executives. Contest their verdict, but stop holding grudges. By all means argue with them but in the end you have to accept a decision or leave elsewhere. So does acceptance of the discipline that keeps us growing while motivation only moves us forward.

The first thing that strikes about the personality of a reporter is their outgoing nature. It does not mean fake expressions, fixed grin on the face, oozing phony friendship,- but the ability to strike up relationships with perfect strangers of recurring assistance. This characteristic is typical for classy reporters- determination, especially visible when information is hard to find.

Anger and sense of injustice are strong characteristics in journalism, informing their judgements about the subjects to be tackled and powering their enquiries in the end. Reporters are not afraid of asking, not because of arrogance, but the passion and empathy. To stay open-minded, journalists not only guard against living inside bubbles of the like-minded, but actively pursue content that challenges their attitudes and preconceived ideas- the contrary.

One of the most dangerous words in journalism is ‘link’. An association between two factors is not proof of a relationship. A great many misleading stories appear because those with an ax to grind announce a relationship between two things and journalists fail to ask enough questions. The result is confusion between a statistical correlation and a casual relationship- it isn’t the same.

A correlation could be, and probably is, a coincidence. A ‘link’ is a word widely used to mean a cause or a supportive cause, but not a connection. Reporters deliberately use ‘linked to’ or ‘associated with’ terminology when the reasons haven’t been proved, nor the potential reasons which could underlie it.

Another type of a story where superficially convincing links catch the unwary are studies raising alarm in political lines by lawyers, such as studies in illnesses, environmental threats, where the data obtained from clustered studies and cherry-picking attempt to produce the desired results.

Sources frequently exaggerate projections. The most common method is to take the highest possible growth rate and apply it way beyond the time when it rises early and would fall apart. Taking the year’s most productive day, multiplying by 365 and then adding the estimate for different kinds of losses. Question what was the turnover from previous year and how to arrive at this sum that with estimated losses results a several times turnover from what was actually achieved.

Calculating probability is specialized and useful when reporting ‘astonishing’ coincidences. Investigative reporting on the contrary isn’t a summary of data but original research that includes extensive interviewing, or matching and comparing the facts and figures and discovering previously unknown patterns.

Knowledge of the lay of public access to information is vital. Most bureaucracies do not exactly advertise the existence of such information and they erect all kinds of barriers to prevent people consulting them- by making it available only at certain times, or by storing them out of the way.

Computer literacy means not just the search efficiently online but also ability to use database software. One of the most instructive investigative reporting was that by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1989 for a series of analyzing racial discrimination in bank lending. The investigation, by reporter Bill Dedman, started with an off-hand remark by a white housing developer that building houses in South Atlanta is troublesome because banks wouldn’t give loans. As Dedman wrote: ‘All we at the paper did, to put it simply, was to cross index the federal computer tapes with a federal census tape, looking especially at comparable black and white neighborhoods.’ This was easier said than done. The first three days were devoted entirely to putting spaces between the numbers on the computer so they could be read properly.

It’s vital to keep up with new technologies, and make them accessible to learn. But doing so is no substitute for the much demanding process of mastering the skills to do research and turn it into compelling and fairly written reports. Acquiring skills needed to do good reporting takes years, and the stage that follows continuously improving abilities- is a career long project. But then, to be called a reporter isn’t so much a job description as a diagnosis. In some professions it is the best complementary diagnosis.

I found this book particularly insightful for qualitative analysis and planning of Customer Surveys and Option Pools, but also resourceful examples by honorable and successful professionals in the history of journalism.

Ref: The “Universal Journalist” 6th edition, David Randall and Jemma Crew, published by: Pluto Press in 2021, ISBN 978-0-7453-4326-6.