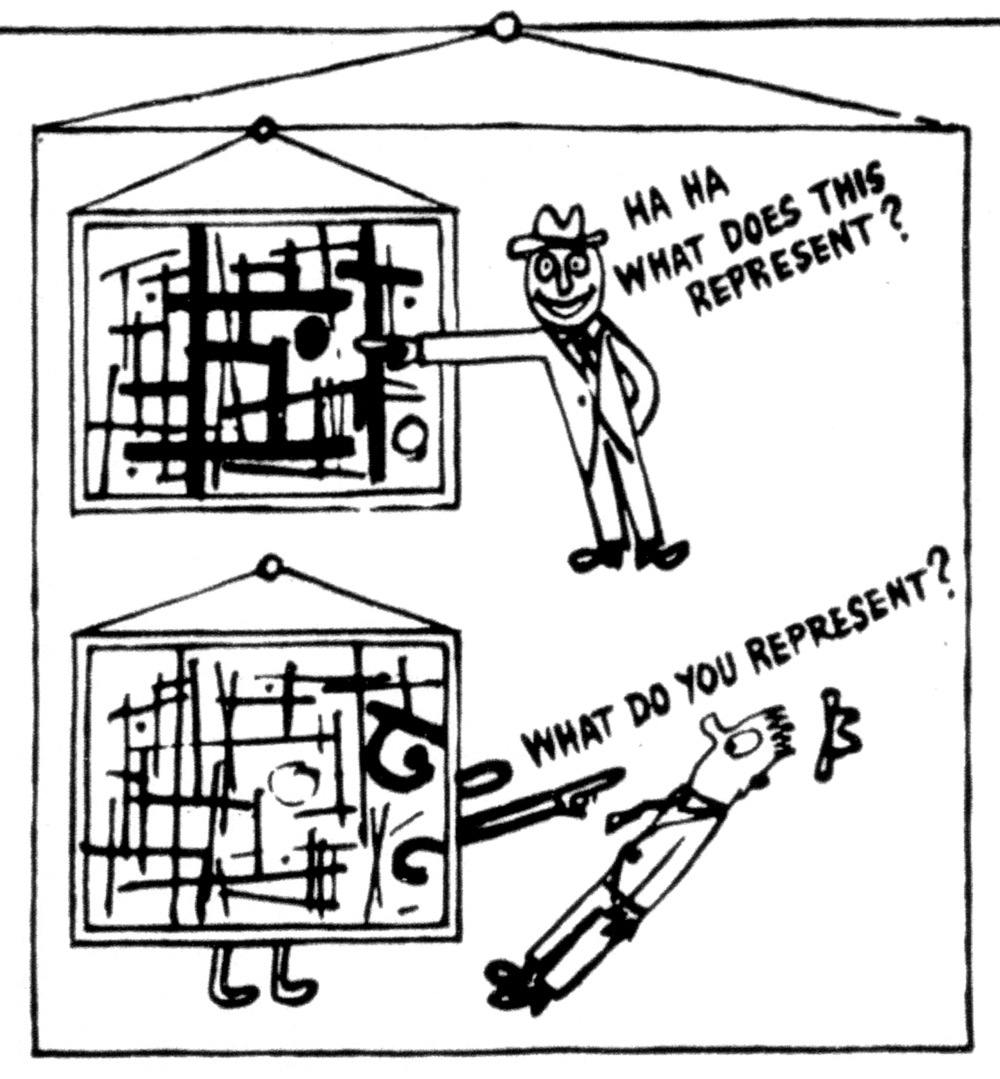

Ad Reinhardt, detail from “How to look at cubist painting”

Agility is our ability to respond to a change while continuing to provide value. It is an attitude, not a technique with boundaries. Agile mindset is the answer- acting in an agile way when the market, technologies, our expertise and value has ever changed.

In infinite games, like business or politics or life itself, the players come and go, the rules are changeable, and there is no defined endpoint, but we always need to improve and keep changing. “The Infinite Game”, written by Simon Sinek.

The practice of fixed language is rather fixated on statements that are right or wrong, growth open-mindset brings more positive attitude and some improvements. But the language of agile mindset is- should we be learning it now, and how can we do better that brings value now?

My takeaway from February are these three books with a broad range of respective work in criticism, analytical practices in research, and language to be understood universally. I draw parallels in my work and life, and with a given example of the transcription from the discussion panel I was honored to attend in Berlinale 2023 International Film Festival in Berlin.

Why Art Criticism?

Given the dominance of the market in the artistic field, it has been said that neither discursive space nor knowledge of context are still required. Criticism would therefore always participate in inescapably problematic processes of canonization that affirm social conditions and serve the market in equal measure.

The skills, responsibilities, and fields of critics, historians, and curators have intermingled; art criticism has allegedly lost its ability to make judgements, reduced at best to interpretations. Criticism thus either acts in sales mode, or fosters notions of fusing the critical text with the object of critique.

The journal October since 1976 has made a significant contribution to focusing attention on art’s potential to be critical in its own right- The criticality of artistic work quickly became the key marker of value in art. The rational, Western, overwhelmingly male subject of criticism has apparently suppressed the physical, sensual and affective elements of it, disparaging them as purely subjective. There also remains the urgent question of who is ultimately permitted to speak for whom, and in whose name, especially when it comes to socially engaged criticism.

So what is to be done with art criticism?

By shifting the subject of attention, art criticism can govern processes of canonization- and is also able to shed light on the justifications and categories behind these processes- even establishing new paradigms for evaluation. With such a tableau, however, the already-blurred line between art criticism and art history becomes even hazier. This reader, however, does not seek to mark boundaries; its aim is rather to make visible the variety of tasks and roles that art criticism could assume.

New approaches to writing have continually been introduced throughout the history of art criticism, with the differences of form being at times so pronounced that it pays to divide the texts into genres. Examples of this are numerous: the Yugoslavian critic Jesa Denegri chose the interview as a way to do formal justice to the diversity of art currents in 1989, both one-on-one dialogue and in conversation with larger groups. In 1801, German poets Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim invented a fictitious dialogue in order to approximate a painting by Caspar David Friedrich. Around a hundred years later, Zuckerkandl in Vienna got involved in a dispute about paintings Gustav Klimt had been commissioned to create by the city’s university; for this she chose the form of the leak, publishing excerpts from letters addressed from the ministry to Klimt and not intended for public consumption. Yet another hundred years later, Australian art critic Jennifer Higgie deployed the serial format to give visibility to women artists: she posts an image of a female artist on social media every day. Even the recommendations website Yelp has been used as a platform for art criticism.

Critical literacy isn’t automatically possessing art criticism- embracing many journalistic formats, including the reviews, reportage, comment, portrait, interview.. Intention to educate about art or to popularize it, including contributions to art historiography, the analysis of an oeuvre, a catalog raisonné, or an art theory. Criticism only makes sense if it functions as a constant, inspiring dialogue. This journalistic commitment calls for both passion and courage, where criticism is governed by interdisciplinary, intermediary thinking.

The various genres and formats- interview, fictional dialogue, leaks, serial chronicles, catalog texts, reviews- are closely interlinked with the platforms they appear on. The form is made by developments in the media landscape, from the emergence of magazines and daily newspapers to the mass media channels. These transitions between old and new media are fluid at times; almost all publications that began in analogue form now also have digital versions. Digitalization has transformed criticism closer to activism and politicization, previously unable to get past the editorial of printed publications.

From a Rauchenberg’s quoted remark “in the gap between art and life, neither can be made” breaks down the boundaries between real elements and traditional artistic materials such as paint. That the medium does not exist except in potential; it is always about to become, but never is for the very action or work that describes it in turn prevents its definition.

The task here is to define and engage critically “photographic discourse” can be defined as an arena of information discourse relation, to this limiting function that determines or situates oneself outside in fundamental criticism.

On what grounds do I establish a judgment of narrative quality? in relation to these imagery artifacts, th Hine and the Stieglitz that I like/dislike, am moved/unmoved- the problem is that every possible move within these reading systems devolves almost immediately into a literary invention with a trivial relation to the artifacts at hand, the illusory status.

In 1942, a portion of Stieglitz’s memoirs was published in Dorothy Norman’s journal Twice-A-Year, including the text “How The Steerage Happened”.

‘’Early in June, 1907, my family and I sailed for Europe. My wife insisted upon going on the “Kaiser Wilhelm II”- the fashionable ship of the North German Lloyd at the time… One couldn’t escape the noveaux riches. On the third day I finally couldn’t stand it any longer: I had to get away from that company. I went as far forward on deck as I could… I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that of the feeling I had about life and this seemingly new vision that held me- people, the ship and ocean and the sky, and the release from the mob called the rich- Rembrandt came into my mind…”,“How you seem to hate these people in the first class.- No, I didn’t hate them, but I merely felt out of the place.” An ideological division is made that suggests separation of the level of report, of empirically grounded rhetoric and level of subjective; photograph us taken at the intersection of two worlds: a world that entraps and the world that liberates- looking out, as it were.

“It is the idyll to which improvisation belongs as a necessary gesture because it cannot bear a pose: our idyll. We can only ever arrive at celebration with improvisations, gaining tranquil moments from so many forms of turmoil. Our idyll’s possibilities lie in the conversational lulls of our addiction, in trembling glances that grasp at serendipitous peace, in flowing trivialities that only a sensation familiar to change is able to hold fast; that is, to preserve them in chance form. They seldom become real: our world is devilishly un-idyllic. But should it succeed, no price is too high.”, Julius Meier-Graefe, from Entwicklungsgeschichte der Moderne Kunst: vergleichende Betrachtungen der bildenden Künste, als Beitrag einer neuen Ästhetik (Modern Art: being a contribution to a new system of aesthetics), 1904

Ref: Why Art Criticism? A Reader (Hatje Cantz Text): Beate Söntgen, Julia Voss. Published by Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH, a Ganske Publishing Group Company, ISBN 978-3-7757-5074-5

Speculations on Subversive Curating

Azar Mahmoudian is an independent curator and educator based in Teheran and Vienna. Since 2020 she has been running the collective study program, A Summer School: For a Summer Yet to Come, in Tehran.

“One of the main issues that set the ground by working as a curator is autonomy of inside/outside and dealing with different forms of isolation. The basic idea of representation from the inside to the outside world has affected the art scene throughout the history of visual arts. The need for representing the emerging artists and underrepresented groups internationally started with globalization and 90s, especially demanding in context of political events.

Job opportunities for a young curator demand creation of programs or exhibitions framing artists into formed opinion polls and their input malfunction. But it isn’t a transition of phase that happened after two decades of closure of the country. The first programs to build a new media image of Iran through cultural diplomacy, making an investment into Islamic culture were produced for exhibit internationally, while not having infrastructure in place to build relations with academic institutions and exchange programs within Iran.

Stated as a main narrative to correct the gaze- educate the gaze- gaze back to the gaze, until setting a common ground for it. For a long time I unreacted, withdrawing from any exhibitions only with Iranian artists for over ten years.

I keep discovering what is the role of curator in different economies and forms of a setup with encounters that bring attention to the cultural scene. Forum Expanded reflects on the medium of film, socio-artistic discourse and a particular sense for the aesthetic that is accessible to the public with quality and not necessarily quantity measure.”

Tobias Hering is a freelance curator whose work focuses on thematic film programs that deal with questions of image politics and the role of archives. He lives and works in Berlin.

“Language has unmistakably made plain that memory is not an instrument for exploring the past, but rather a medium. It is the medium of that which is experienced, just as the earth is the medium in which ancient cities lie buried. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging (or a woman). Above all, he (or she) must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil. ..

And the man (or a woman) who merely makes an inventory of his findings, while failing to establish the exact location of where in today’s ground the ancient treasures have been stored up, cheats himself of his richest prize.

In this sense, for authentic memories, it is far less important that the investigator report on them than that he mark, quite precisely, the site where he gained possession of them.

Epic and rhapsodic in the strictest sense, genuine memory must therefore yield an image of the person who remembers, in the same way a good archaeological report not only informs us about the strata from which its findings originate, but also gives an account of the strata which first had to be broken through.”

Ref: Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 2, part 2 (1931–1934), ”Ibizan Sequence”, 1932.

“It appoints the position of one who remembers or does research which is why it relates to my practice as a curator and more in dealing with an archive work and prior research. This positioning is physical and becomes a measure for a distance in a work, a measure of distance in time. But also distance to the place in relation to the objects- the places of texts, films, but also place where to find, or where we would expect to be found.

It’s always good to keep myself within the picture to be aware of what these objects do to myself and my practice, and sometimes transport back to the places and get older to find or even be able to relate.

Irena Vrkljan, “Schattenberlin” Aufzeichnungen einer Fremden 1990, ISBN: 9783854201908

I also put this quote to give an example with my current currational work, a film by Irena Vrkljan. She was a Croatian writer, poet, scriptwriter and filmmaker. I came across her first as a student in the Film Akademie in Berlin and she was one of the first three women of her generation starting the school and made four remarkable films, included in two curator programs in the last 7 years.

The four films that Vrkljan made in Berlin are a dowser’s explorations of a location, stories of “Schattenberlin” (the title of a novel published in 1990), but also critical positions on the politically active dffb generation. Benjamin was an important reference in this book; he’s one of the several protagonists in the city, along with the other people who had been forced to exile and emigrate or who came to Berlin as emigrees, who’s lives and trajectories she follows.

Widmung für ein Haus (1966) is a cinematic homage to the legendary “Haus Vaterland“ in Potsdamer Platz, the ruins of which stood in the no man’s land between West and East Berlin. Widmung für ein Haus and Berlin unverkäuflich (1967) was digitized by Johannes Beringer and included in the archives in early 2000. Film will be screened again in June during the short-film festival in Hamburg.

Erika Balsom is a scholar and critic based in London, working on cinema, art, and their intersection. She is a reader in Film Studies at King’s College London.

To get to one example from a project that was held in Haus der Kulturen der Welt last summer, called “No Master Territories. Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image”. This was a project that looked at a range of non fiction films and videos by women from places around the world primarily from 70s to 90s. We didn’t run into issues for work we planned to show, and there’s something to be said about privilege working with an institution that has a protector and facilitator function.

We didn’t include any content notes but the one large difficulty we ran into while dealing with the national archive was the film observational documentary about violence against women produced for a national broadcast.

We were interested in it as a document the legal system reproduces, but also as a nucleus of a larger constellation of works made by these women: documents, tv shorts, 8mm super 8 portraits and this film.

But we were told we couldn’t show the work. The reason was one of the man who appears in the film, one of the defendants had contacted the archive and invoked his right to be forgotten. It was not a legal proceeding but an individual contacting an archive for distribution of film. Notably the film is available on YouTube. The right to be forgotten in EU privacy legislation is mostly concerned with internet search results, asking certain kinds of information to be removed from. Idea of invoking this in relation to historical film is, I think, terrifying and brings interesting questions.

The right to be forgotten has to be balanced against the right to free expression and public rights information. These would weigh in relation to one another and different jurisdictions around the world evaluate it in different ways, for instance, in the right to be forgotten US it does not exist like in Europe.

So here we are with the convicted criminal and the filmmakers. We asked lawyers to see if there is anything we could do, but the revisions of legislation would not resolve the issue and we were suggested to show only QR code that would link the film to YouTube. Then we reached out to the Copyright lawyer and he was fascinated and hoped we would show the film and be sued. This would make more impact than an exhibition ever will.

But we didn’t want to be sued, and the last option was going back and asking for tolerance rather than permission- ask them to ignore the fact that we would show the film without the rights, and this is exactly what we did. Some institutions would not sign up for this and would not show the film. But also it made me question, should this man indeed have the right to be forgotten? What’s that stake in continuing the circulating film about criminal proceedings forty years after the fact.

I would like to add one final remark about the question of labor and working conditions. When we talk about subversive curating, there’s a real question in terms of who can risk being subversive in a particular context. One way is to work outside institutions or build alternative institutes, or take refuge in institutions and be protected by it, but increasingly it can’t happen and looks more of a fiction.

“Festival programmer jobs, just like film critics’ jobs, have become the stuff of fiction. It would seem that full employment in our field is something that ended with the 20th century. Filmmakers and programmers are paid with “exposure”—but as someone once pointed out during a Podium discussion in Oberhausen, “people die from exposure.”” María Palacios Cruz article “A festival is a labor of love, but the confusion of love and labor is complicated.”

Transcript from Speculations on Subversive Curating Discussion event, reflected upon: What are the strategies that curators are adapting to avoid self-censorship in which cultural policies and ideologies of nation states determine what can and cannot be screened?