https://player.vimeo.com/video/386757761?h=c549f73bae&dnt=1&app_id=122963

Christine Groult – November 23rd, 2019, https://issueprojectroom.org/video/christine-groult

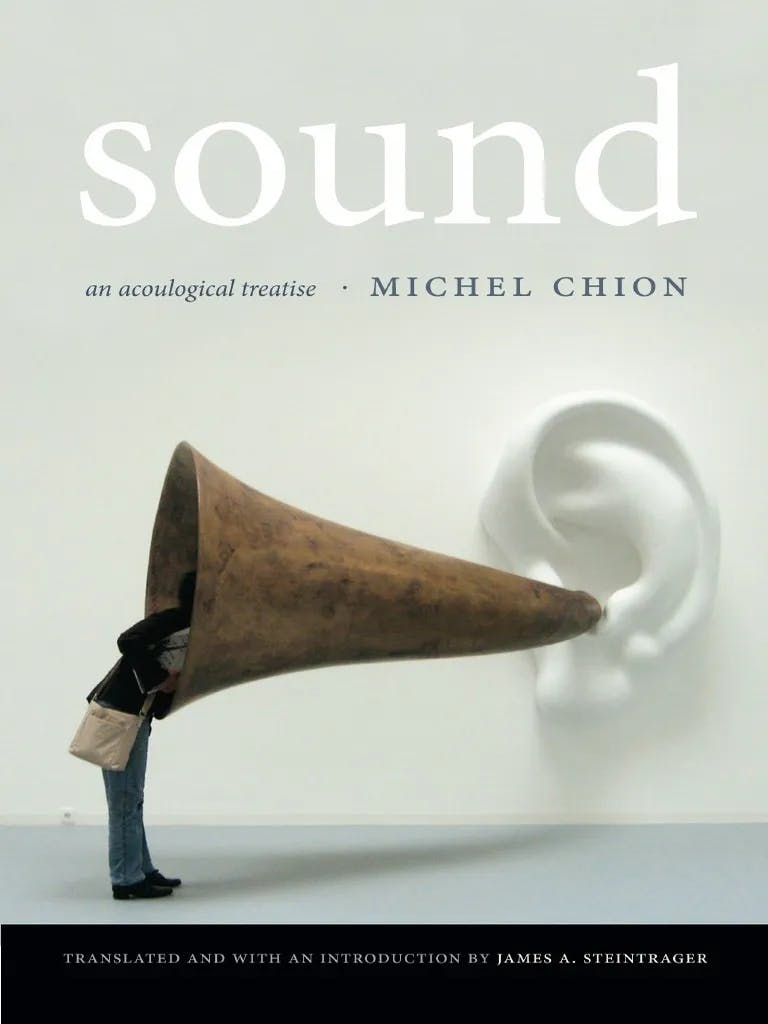

The objective of the Michel Chion’s landmark Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen has exerted significant influence on our understanding of sound-image relations since its original publication in 1993. It is to demonstrate the reality of audiovisual combination—that one perception influences the other and transforms it. We never see the same thing when we also hear; we don’t hear the same thing when we see as well. We must therefore get beyond preoccupations such as identifying so-called redundancy between the two domains and debating interrelations between forces (the famous question asked in the seventies, “Which is more important, sound or image?”).

This work is at once theoretical and practical. First, it describes and formulates the audiovisual relationship as a contract—that is, as the opposite of a natural relationship arising from some sort of preexisting harmony among the perceptions.

Visual and auditory perception are of much more disparate natures than one might think. The reason we are only dimly aware of this is that these two perceptions mutually influence each other in the audiovisual contract, lending each other their respective properties by contamination and projection.

“fixed sound” is that which entails no variations whatever as it is heard. This characteristic is only found in certain sounds of artificial origin: a telephone dial tone, or the hum of a speaker. Torrents and waterfalls can produce a rumbling close to white noise too, but it is rare not to hear at least some trace of irregularity and motion. As the trace of a movement or a trajectory, sound thus has its own temporal dynamic.

Sound perception and visual perception have their own average pace, where the ear analyzes, processes, and synthesizes faster than the eye, but not a matter of attention. For hearing individuals, sound is the vehicle of language, and a spoken sentence makes the ear work very quickly; by comparison, reading with the eyes is notably slower, except in specific cases of special training, as for deaf people. The eye perceives more slowly because it has more to do all at once; it must explore in space as well as follow along in time. The ear isolates a detail of its auditory field and it follows this point or line in time. In a first contact with an audiovisual message, the eye is more spatially adept, and the ear more temporally adept.

The ear’s temporal threshold

Further, we need to correct the formulation that hearing occurs in continuity. The ear in fact listens in brief slices, and what it perceives and remembers already consists in short syntheses of two or three seconds of the sound as it evolves. However, within these two or three seconds, which are perceived as a gestalt, the ear, or rather the ear-brain system, has minutely and seriously done its investigation such that its overall report of the event, delivered periodically, is crammed with the precise and specific data that have been gathered.

This results in a paradox: we don’t hear sounds, in the sense of recognizing them, until shortly after we have perceived them.

Clap your hands sharply and listen to the resulting sound. Hearing—namely the synthesized apprehension of a small fragment of the auditory event, consigned to memory— will follow the event very closely, it will not be totally simultaneous with it.

The three listening modes

When we ask someone to speak about what they have heard, their answers are striking for the heterogeneity of levels of hearing to which they refer. This is because there are at least three modes of listening, each of which addresses different objects. We shall call them causal listening, semantic listening, and reduced listening.

Causal listening

Causal listening, the most common, consists of listening to a sound in order to gather information about its cause (or source).When we cannot see the sound’s cause, sound can constitute our principal source of information about it. An unseen cause might be identified by some knowledge or logical prognostication; causal listening (which rarely departs from zero) can elaborate on this knowledge.

In some cases we can recognize the precise cause: a specific person’s voice, the sound produced by a particular unique object. But we rarely recognize a unique source exclusively on the basis of sound we hear out of context. Even though dogs seem to be able to identify their master’s voice from among hundreds of voices, it is quite doubtful that the master, with eyes closed and lacking further information, could similarly discern the voice of her or his own dog.

Semantic listening

I call semantic listening that which refers to a code or a language to interpret a message: spoken language, of course, as well as Morse and other such codes.

Obviously one can listen to a single sound sequence employing both the causal and semantic modes at once. We hear at once what someone says and how they say it. In a sense, causal listening to a voice is to listening to it semantically as perception of the handwriting or code of a written text is to reading it.

Reduced listening

Pierre Schaeffer gave the name reduced listening to the listening mode that focuses on the traits of the sound itself, independent of its cause and of its meaning.

Reduced listening takes the sound— verbal, played on an instrument, noises, or whatever—as itself the object to be observed instead of as a vehicle for something else.

A session of reduced listening is quite an instructive experience. Participants quickly realize that in speaking about sounds they shuttle constantly between a sound’s actual content, its source, and its meaning. A form of retreat involves entrenchment in out-and-out subjective relativism. Every individual hears something different, and the sound perceived remains forever unknowable. But perception is not a purely individual phenomenon, since it partakes in a particular kind of objectivity, that of shared perceptions. And it is in this objectivity-born-of-intersubjectivity that reduced listening, as Schaeffer defined it, should be situated.

In reduced listening the descriptive inventory of a sound cannot be compiled in a single hearing. One has to listen many times over, and because of this the sound must be fixed, recorded. It has the enormous advantage of opening up our ears and sharpening our power of listening.

When we identify the pitch of a tone or figure out an interval between two notes, we are doing reduced listening; for pitch is an inherent characteristic of sound, independent of the sound’s cause or the comprehension of its meaning.

What complicates matters is that a sound is not defined solely by its pitch; it has many other perceptual characteristics.

Can a descriptive system for sounds be formulated, independent of any consideration of their cause? Schaeffer showed this to be possible, but he only managed to stake out the territory, proposing, in his Traite des objets musicaux, a system of classification. This system is certainly neither complete nor immune to criticism, but it has the great merit of existing.

Acousmatic sounds

Acousmatic, a word of Greek origin discovered by Jerome Peignot and theorized by Pierre Schaeffer, describes “sounds one hears without seeing their originating cause.” Radio, phonograph, and telephone, all which transmit sounds without showing their emitter, are acousmatic media by definition. The term acousmatic music has also been coined; composer Francis Bayle, for example, uses it to designate concert music that is made for a recorded medium, intentionally eliminating the possibility of seeing the sounds’ initial causes.

What can we call the opposite of acousmatic sound? Schaeffer proposed “direct,” but since this word lends itself to so much ambiguity, we shall coin the term visualized sound—i.e., accompanied by the sight of its source or cause. In a film, an offscreen sound is acousmatic.

Offscreen sound

Passive offscreen sound is sound which creates an atmosphere that envelops and stabilizes the image, without in any way inspiring us to look elsewhere or to anticipate seeing its source. Passive offscreen space does not contribute to the dynamics of editing and scene construction—rather the opposite, since it provides the ear a stable place (the general mix of a city’s sounds), which permits the editing to move around even more freely in space, to include more close shots, and so on, without disorienting the spectator in space. The principal sounds in passive offscreen space are territory sounds and elements of auditory setting.

In 1954 Rear Window included much passive offscreen sound: city noise, apartment courtyard sounds, and radio, which, full of reverb, cued the ear into the contextual setting of the scene without raising questions or calling for the visualization of their sources.

Offscreen trash

The offscreen trash is a particular case of passive offscreen space that results from multitrack sound. It is created when the loudspeakers outside the visual field “collect” noises—whistles, thuds, explosions, crashes—which are the product of a catastrophe or a fall at the center of the image. Action and stunt movies often draw on this effect. Sometimes poetic, sometimes intentionally comic, the “offscreen trash” momentarily gives an almost physical existence to objects at the very moment they are dying.

Sound fidelity

But when we say in disappointment that “the sound and image don’t go together well,” we should sometimes blame it exclusively on the inferior quality of the production.

Someone who listens to an orchestra on a sound system in his living room is not likely to be able to compare it with some orchestra playing at his doorstep. It should be known, in fact, that the notion of high fidelity is a purely commercial one, and corresponds to nothing precise or verifiable.

Consider the children’s books that teach the noises animals make: as if there were the slightest connection, aside from the connection created by purely Pavlovian training, between the sound a duck makes and what it looks like, or the onomatopoetic words for the duck’s call in different languages.

The role of the sound

Today’s multipresent sound has insidiously dispossessed the image of certain functions—for example, the function of structuring space. But although sound has modified the nature of the image, it has left untouched the image’s centrality as that which focuses the attention. Sound’s “quantitative” evolution—in quantity of amplification, information, and number of simultaneous tracks—has not shaken the image from its pedestal. Sound still has the role of showing us what it wants us to see in the image. From that image we can see only one side of things, only halfway, always changing.

Yet there is only one element that the cinema has not been able to treat this way, one element that remains constrained to perpetual clarity and stability, and that is dialogue.

Narrative analysis

A sound-image comparison is also in order on the level of narration and figuration. To do this we might start by asking, What do I hear of what I see? and What do I see of what I hear? When the projection onto the image as well as the sound isn’t explicitly shown, much less named leaving the impression of synchronization points, for she or he can’t help but be aware of discontinuity and context of nonpatterns.

Ref: Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen by Michel Chion